This Grief Thing: Helping people to talk about grief

Photograph: This Grief Thing Middlesbrough 2018 by Fevered Sleep

Following the devastating and sudden death of his sister, David Harradine, Co-Artistic Director and CEO of arts production company Fevered Sleep, launched This Grief Thing.

We live in a time when many people find grief impossible to talk about. David explains how This Grief Thing aims to normalise conversations about grief, helping people to support each other through a universal human experience.

It’s 24 November 2011, the night my life changed. 6:50pm, and I’m in my studio in London, editing a short film about ageing and time. My phone rings. My sister-in-law’s voice, “David… I don’t know how to tell you…”. In the background, my mum, wailing, screaming, pain. A sound I will never, ever forget. “David… I don’t know how to tell you…”

On 24 November 2011, my life changed. My older sister, my closest sibling, had died in a car accident. Immobilised with shock, I called my partner. He came to collect me. We drove back to our flat. In the kitchen, I smashed things up. We got in the car, we drove up the A1 to my parent’s house in Yorkshire, the house where I grew up, and I stayed there for the next three months, in a house of grief, in shock, in my childhood bed, trying to help my parents, trying to come to terms with what had happened.

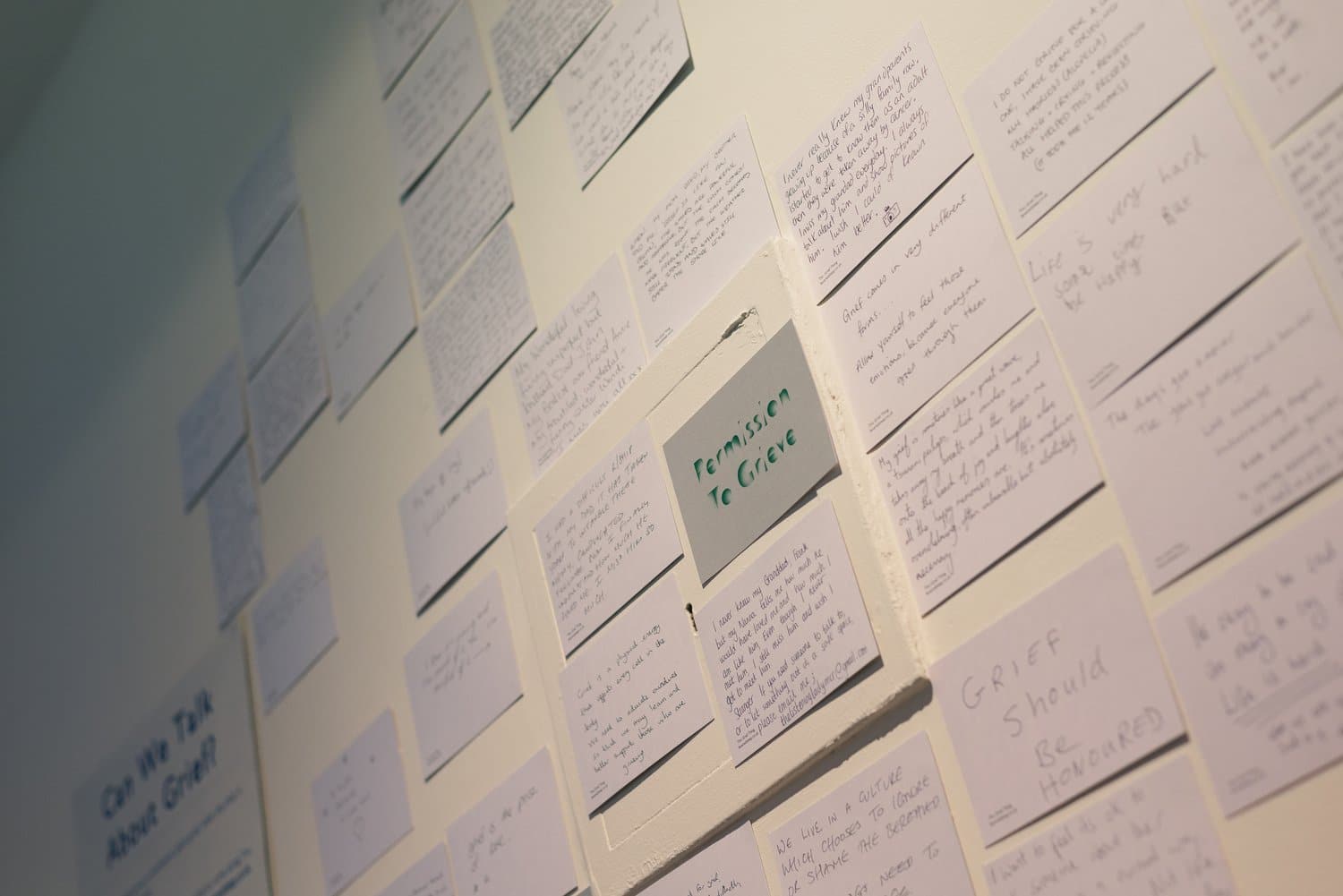

Again and again, we heard about invisible grief, unacknowledged grief, grief that had to be hidden, silenced, ignored. We talked about mourning clothes, about wearing black, or arm bands, about the different rituals in different cultures and religions and countries, all the different ways that grief could be worn on the surface of the body: “I’m still grieving: talk to me about it.”David Harradine

During that time, I felt completely disconnected from my former life. I stopped working, focused completely on my parents and all the ways I might be able to help them survive this loss. Cooking for them, eating together, crying together, visiting my sister’s grave. I tried to fill the abyss that she had left behind; trying to take up the space of two children; trying to produce that much love.

For myself, I felt as though a veil had lifted, a veil that had been obscuring a whole emotional landscape that I didn’t know existed. A landscape of loss, and death, and grief; a landscape I was completely lost in, confused and angry and heartbroken; a landscape for which I had no map.

I am lucky. I work in the arts. I’m co-artistic director of an arts production company called Fevered Sleep. My friends and colleagues are in tune with their emotions, sensitive and articulate, and they were amazing; an amazing support, unafraid of my grief, it seemed; able and willing to acknowledge it. My mum had a very different experience: seeing people turn away when they saw her in the supermarket; going out for coffee with friends who didn’t ask her how she was. As though being a grieving mother was a disease, something contagious, something to avoid. Or something just too awful to acknowledge. But one by one by one, my friends also stopped asking how I was, how my parents were; stopped asking about my sister. After a few months, everybody else seemed to be back to business as usual. Me? I was still in the thick of grief, still in shock, still bewildered, and increasingly angry and disappointed that those people who had been so amazing at the start had one by one by one forgotten to ask how I was; had forgotten how to see and acknowledge my grief.

One day I said to Sam Butler, Fevered Sleep’s other artistic director and my best friend, “I want to make a T-shirt that says: ‘I’M STILL GRIEVING: WHY HAVE YOU STOPPED TALKING TO ME ABOUT IT?’”. Without hesitation, Sam said, “Let’s do that, let’s make that happen, let’s make that for you”. And so our project This Grief Thing was born.

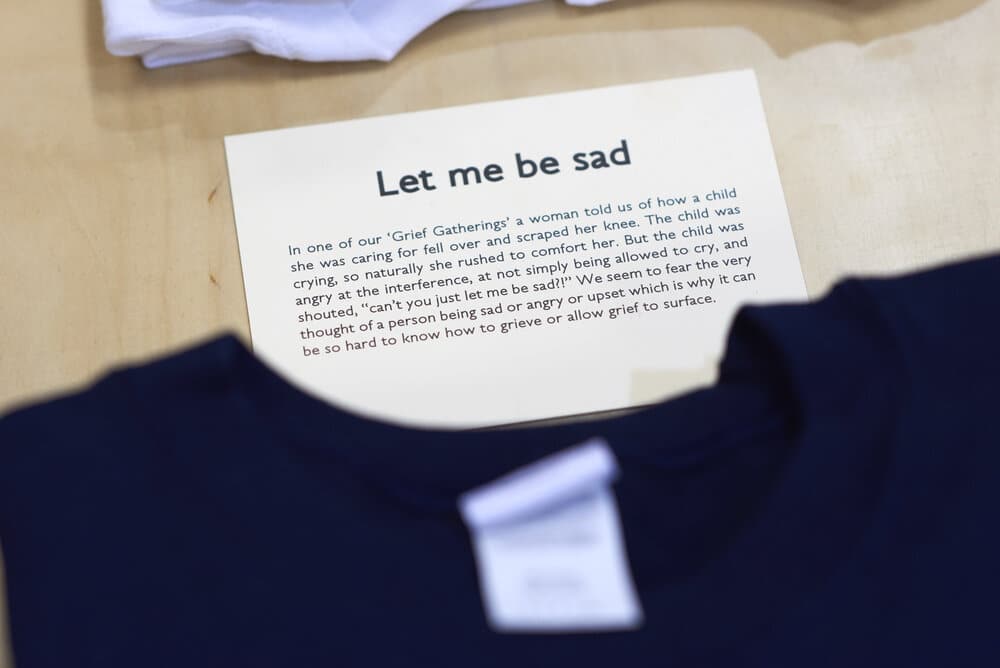

We began as we always do when we’re making a new project: by talking with other people about the thing we are working on. Over several months, we travelled the country, meeting small groups of people to talk about grief. We gathered stories, advice, words and phrases that we heard repeatedly. Words that attempted to describe grief; words that might be useful for someone who’s grieving: Grief is like the weather. Grief = Love. Don’t panic if I cry. Let me be sad. There will be joy again.

Again and again, we heard about invisible grief, unacknowledged grief, grief that had to be hidden, silenced, ignored. We talked about mourning clothes, about wearing black, or arm bands, about the different rituals in different cultures and religions and countries, all the different ways that grief could be worn on the surface of the body: “I’m still grieving: talk to me about it.”

Sam and I worked with a graphic designer, Fraser Muggeridge studio, and made a collection of clothing – T-shirts, jumpers, scarves – as well as things like cards and brooches and badges. Every item showed one of the phrases that we’d gathered through those conversations about grief: Let me be sad; Grief = Love; Don’t panic if I cry

Once we’d made this collection, we travelled around England, opening pop-up shops. The shops became places for people to gather to talk about grief. We sold the items on a pay-what-you-want basis (someone might pay 50p for a jumper, someone else £50). Hundreds and hundreds of people came to talk, to listen, and to learn about grief. When the shops were closed, we held more conversations, which we called Grief Gatherings. These became a vital, central part of the project, and when the pandemic arrived in 2020, and meeting in person was no longer possible, we moved the Grief Gatherings online. Suddenly we found ourselves in conversations with people all over the world: people in the UK talking with people in Canada and Australia, France and Belgium and the USA. As the project grew, we invited other people to host conversations for us. Brilliant guest hosts engaged people from their own communities. Deaf actress and producer, Deepa Shastri, held Grief Gatherings in BSL; queer activist Dan de la Motte held gatherings for LGBTQ people; multidisciplinary artist Lou Robbin held them for people from the Global Majority.

This Grief Thing has tried to make grief more visible. It’s an attempt to normalise grief, to insist that it’s a normal, healthy emotion that shouldn’t be hidden or suppressed; that grief isn’t something to be ashamed of.David Harradine

In 2021, we put together a whole programme of events in London: we opened market stalls instead of shops; we ran a billboard and poster campaign, trying to make grief visible in public spaces; we did many more Grief Gatherings; we commissioned artists Akshay Sharma and Rayvenn d’Clark to make work on the theme of grief. We also curated a series of online conversations on grief, which brought together various ‘grief experts’ to talk about grief from their own perspectives. An artist with a philosopher; a death doula with an academic; a photographer with a bereavement counsellor; a theatre-maker with a fashion historian. If you’re interested, you can find recordings of these conversations on our website.

In all these different ways, This Grief Thing has tried to make grief more visible. It’s an attempt to normalise grief, to insist that it’s a normal, healthy emotion that shouldn’t be hidden or suppressed; that grief isn’t something to be ashamed of. Through all the many conversations we’ve had with people about grief, in the shops, in Grief Gatherings, on the street and online, we’ve learned so much, and the project carries this learning from place to place. This Grief Thing is a resource, a community, a declaration, and an attempt to bring grief into the light. Thanks for reading this blog: your engagement is another small step towards acceptance of grief; another small act of radical compassion; another gesture of solidarity in the face of unbearable loss.

As I write, we’re taking a pause from This Grief Thing while we work on new projects. We’ll be doing more Grief Gatherings and another online programme in summer 2023, and all the items from the collection are available from our online shop. If you want to keep in touch, sign up to our mailing list and you’ll be the first to know when the project is running. We’d love to see you at one of our events; we all need to talk about grief.

David Harradine is an artist, and co-founder of Fevered Sleep, making performances, installations, films, books and digital art. He’s Professor of Interdisciplinary Practice at The Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, University of London and is a trustee of Yorkshire Dance. Born into a rural, working class community in West Yorkshire, he now lives in York and London.

There’s much more to death than we think; what if it isn’t just an ending, but an event we can plan for? Thinking beyond the four walls of hospices and hospitals, we have the chance to approach it with confidence and plan a good death. After Wards is a collection of insights and ideas from people who can help us all to re-imagine this essential part of life, and to live well until we die.